The usual bird chatter soundtracking through the open kitchen windows shifted abruptly. A cacophony of squawks and screeches outside pulled my attention to the backyard and away from the cookies I was decorating for my daughter Lily’s graduation party.

I saw my two-year-old chocolate Labrador retriever Dewey next to the large maple tree, his blocky head turning swiftly in all directions, following the erratic trajectories of several dive-bombing robins. With their flapping wings and shrieking cries, they were determined to keep his focus trained on them and away from the baby bird at his feet. I raced out the back door, passing our older and wiser yellow Labrador Wally, who was planted a safe distance away from the threats of the adult birds.

“Dewey, come get a treat!” I beckoned. The promise of food was enough to pull him away. I grabbed both his collar and Wally’s and ushered them inside for the promised cookies before returning to the backyard.

Praying that Dewey hadn’t caused damage, I cautiously squatted next to the baby bird, while reassuring the squawking robins with my best I’m a mom, too voice. “It’s okay, I’m not going to hurt it. Everything is okay.” The little thing was frozen in terror, but appeared unharmed. I assumed it had fallen from a nest hidden somewhere in the leafy branches overhead, too far up for me to possibly reach. I wasn’t sure what to do.

I have very little bird knowledge, but a quick Google search on my phone helped me identify the bird as a fledgling—a juvenile that is likely on the verge of flying and ready to leave the nest.

It could, in fact, have even been pushed out intentionally by its mother to encourage its development. Conventional Internet wisdom urged me to leave the young bird while it built up the strength and maturity (under the continued supervision of its parents) to be completely flighted.

The problem, though, was that the ill-chosen training site—lacking in ground cover and often occupied by two curious Labs—was not the optimum setting for a process that can take up to two weeks. And with the dogs around, there was a higher likelihood that the parents might abandon their baby too soon.

Weighing the risks, I wrapped a paper towel around the little bird before carrying it to safety. The fledgling stretched its neck upward and its yellow beak gaped open, clearly hoping I had something for it to eat. Wanting to minimize my intervention, I hurried through the gate and set the bird on the ground near the overgrown bushes that separate our yard from the neighbors’ yard. The baby bird hopped a few feet away and cowered in the dirt underneath a low hanging branch.

I was relieved to see that the adult birds had followed my progress, and they continued their raucous cries from their perches in the trees nearby. Yet despite their reassuring presence, I couldn’t quite convince myself to walk away. I felt torn between allowing nature to take its course and the distressing weight of responsibility to make sure this little fledgling survived the experience of being launched into the world.

My Daughter is Leaving for College

This contradiction of feelings is nothing new for me these days, and even in that moment, the irony of a bird leaving the nest wasn’t lost on me. I’ve recently celebrated my youngest child’s graduation from high school and now she, too, is taking flight from the security of our home to study at the University of Toronto. While I’m genuinely delighted by her accomplishments and eager for what’s ahead, I’m simultaneously gripped by the panic of knowing she’ll be in a massive and unfamiliar city, across a border, and nine hours beyond my reach. And despite the 18 years I’ve devoted to preparing her for this exact milestone, it turns out I am not remotely ready.

Unlike the tough-love bird parents in my yard, I have zero inclination to push her out. Instead, I’m fighting the near-constant desire to latch on tighter, tucking her safely under my wings.

In those still hours of night, when sleep is elusive, a chorus of fretful questions plays through my mind: Will she make good decisions? Will she be safe? Will she be able to take care of herself? Will people be nice to her? Will anyone know if she’s sad? Or scared? Or lonely? How will I know if she’s okay?

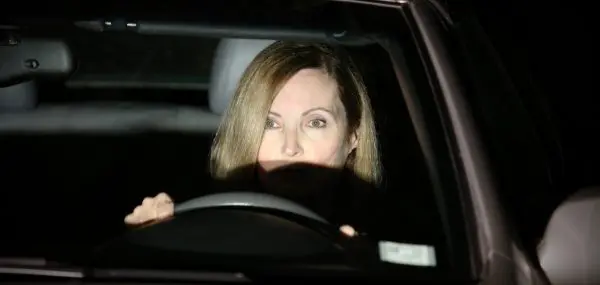

I push back against the looping film of worst-case-scenarios that my catastrophizing imagination can’t stop conjuring. Lily, crying alone in her dorm room because she has no friends. Lily, engulfed in panic after failing an exam and too ashamed to call home. Lily, walking down a city street at night, vulnerable to predators and other unseen dangers lurking in the shadows. After much practice (and much therapy), I can usually convince my anxious brain to halt the amplifying progression of images too nightmarish to even describe. But I can’t deny the persistent voice that’s always there whispering, “It could happen.”

Leaving the Nest

Comparable concerns about the baby bird in the bushes conspired to keep me rooted in place for the remainder of that afternoon, standing guard and doing all I could to protect it. But I knew I would have to surrender to the inevitable reality that I couldn’t control what came next, no matter how much I wanted to. The fledgling could wander into the street and get hit by a car, or be snatched up by a predator, or starve because its mother decided to eventually fly off. All of those things were possible, but the fact that my yard and street weren’t littered with carcasses of other baby birds, and the trees around me sang with the chatter of the birds gathered there, indicated that those things probably wouldn’t happen.

Empirical evidence I’ve collected throughout Lily’s life tells a similar story. From babysitters to teachers to coaches; through kindergarten and elementary school, middle school and high school; with sports teams, overnight camp, and evolving friend groups—Lily has always been able to adapt and thrive. And in those expected moments of transition, whenever things have gotten tough, she’s turned to me for help.

As uncomfortable and counterintuitive as it feels, I have to trust that all of those moments have prepared her—and me—for this next chapter. And I need to keep teaching myself to let go so she can learn to fly on her own.

I crouched down and peered at the fledgling pushing its body tighter against the solid trunk of the bush. Its eyes darted toward me and then searched for the source of the steady call from what I hoped was its mother.

“Be brave,” I whispered. “And please, please be okay.”

Then I stood up, and after a few more seconds of indecision, turned my back and headed inside.