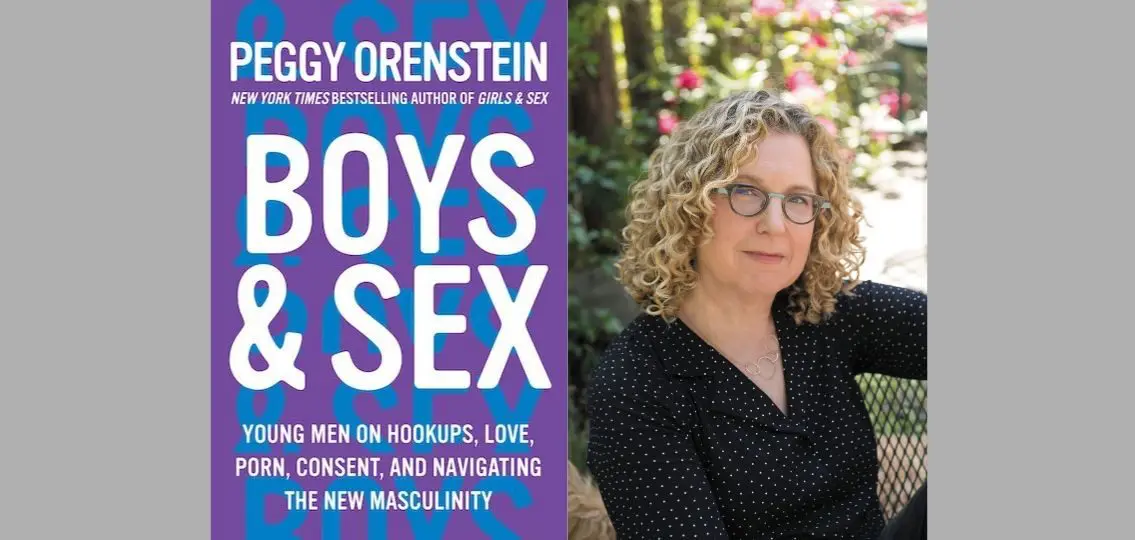

Peggy Orenstein doesn’t shy away when it comes to writing about delicate subject matter. The New York Times best-selling author whose books include Girls & Sex, Cinderella Ate My Daughter and her classic School Girls: Young Women, Self-Esteem and the Confidence Gap takes time to talk with Your Teen about what she’s discovered in researching her latest book, Boys & Sex: Young Men on Hookups, Love, Porn, Consent and Navigating the New Masculinity, released January 2020.

Q: What prompted you to write this book?

Orenstein: I suppose the short answer is I suddenly realized I’d only had half a conversation. I’ve been writing about girls for 25 years. It’s been my calling, my interest, and my passion. But everywhere I went after Girls & Sex came out, people said, what about boys?

Q: How did the process begin?

Orenstein: Honestly, I thought boys wouldn’t talk to me. They don’t have a reputation for chatting the way girls to. Plus, I looked like their mom. I was worried about that. But I found that my concerns were completely unwarranted. These boys were really honest, candid, blunt, and emotional. And they really wanted to talk because nobody had ever talked to them before.

Q: What did you discover about boys?

Orenstein: They suffer differently than girls. A sort of systematic disconnecting from emotion. Boys would talk about how they learn to suppress their emotions. “I trained myself not to feel. I trained myself not to cry.” They worry about appearing weak in front of both other boys and girls. That was really pervasive and profound and heartbreaking.

Q: After writing Girls and Sex and now Boys and Sex, what is the biggest difference?

Orenstein: In terms of sexual pleasure, I found that many girls are disconnected from their bodies. And many boys are disconnected from their hearts.

Q: Did you find that boys don’t know what rape is?

Orenstein: When we talk to our kids about sexuality, it’s really easy actually to go quickly to rape and quickly to consent. While those things are crucial (and I have a lot on my website for parents looking to understand how to have those conversations), I think it’s really important that we recognize that consent just makes sex legal; it doesn’t make it ethical. And it doesn’t make it good. So, we must have these larger conversations about positive sexuality, about sexual ethics, and our values that aren’t limited to yes or no. But what happens after somebody says yes, or after that?

Q: That’s poignant. Could you give one example of a male who believed he got consent, but wasn’t kind?

Orenstein: There was this boy who was very intentional about asking for consent to have sex. He was also very clear that it was only for sex. He wasn’t looking for anything more. He would say, “This is all we’re going to do. We’re just going to hook up. If you want lunch or a movie, that’s not what I do.” He had slept with an enormous number of young women. Finally, one of his male friends said, “I want to spend time with you. But your whole focus is sleeping with every one of my female friends, and then discarding them. And I don’t really want to hang out with you if that’s who you are.” And he started to realize that just because somebody consented didn’t mean he’d treated them well. He thought, “Is this really who I want to be?” Then he had a really interesting transformation and soon after told me that he had a girlfriend and had a very different mindset about sexuality and relationships and his own past.

Q: Clearly, we need to be talking to our boys about more than the biology of sex. How do we do that?

Orenstein: There are things that need to be said to all kids, of course, but also the boys specifically. And the first thing is realizing that it isn’t just “The Talk”. We understand that we wouldn’t say one thing to your kid about table manners and think, “Okay, now they know not to chew with their mouth open.” You have to keep having discussions about sex and relationships and they have to be short and small. Ideally, have these conversations when you’re doing a physical activity or you’re in the car, so you are avoiding direct eye contact. And it’s not just about sex and aggression and rape. In a way it is easier to talk about violence and harm because we’re afraid. We also need to talk about positive sexuality and positive sexual experiences, even though it makes us squeamish with our kids.

Q: You quote Michael Holmes in your book, “Silence in the face of cruelty and misogyny is how boys become men.”

Orenstein: That is something that we really deeply need to reckon with. How do we support boys? Many boys I spoke to want to stand up but they are afraid to. Boys who step up often become marginalized by their peer group. How do they choose between their dignity and their friends? How do we help our boys so that they can be the full human beings that they deserve to be and the men we know that they can be?

Q: Can you share a surprising moment during your research?

Orenstein: I asked a boy what the most intimate moment was for him. And he said holding hands. He only held hands with people he really cared about.

Q: Wow. Do you see his response in any way connected to today’s easy access to porn?

Orenstein: Absolutely. Porn is sex without intimacy. The only part of people’s bodies that touch is their genitals. They don’t caress. They don’t kiss. It’s not even passionate. There is no intimacy or passion or vulnerability in porn. When our boys watch porn, they learn that sex isn’t the most intimate act. Boys in particular are looking at porn before they even ejaculate for the first time, before they’ve kissed a girl, before they’ve gone on a date. They use porn as sex education. It’s affected their view of what sex is and how it should happen. And that is an impoverished and sexist view of human sexuality.

Q: You mentioned one boy who was using a flip phone in response to his overuse of porn. What was his story?

Orenstein: This boy was using a flip phone to control his porn overuse. (Most porn is watched on smart phones.) I asked this boy when he’d first had sex and his answer was, “Last Friday.” He’d had a long history of extreme porn use, but he’d never actually had a real sexual encounter. His first few tries with a girl were unsuccessful. He and the girl ended up having a long conversation about their attitudes about sex, about anxiety, about friendship, about love, about themselves for over two hours. He said it was like a storybook then. It all worked magically. I asked him what he learned. He said that the human body is a vulnerable thing. You can’t learn that from a video screen.

Q: What can parents do about porn?

Orenstein: Unfortunately, you’re not going to be able to block your way out of this. But I think a couple of things. One is making sure your child has ample access to accurate ethical sex ed resources in the home and online. If you look on my website, there are all kinds of resources for kids. Also, I would have them read my chapter on porn. It provides many perspectives from other boys. The boys I interviewed really wanted to talk about porn. They really wanted to know that it was normal, how it would affect their sexual functioning. I really want boys to know that porn actually undermines your sexual satisfaction in real life.

Here’s one thing parents can say. “Porn will make you less satisfied with your partners’ bodies, with your own performance, and with your sexual experience. Do you really want to be doing something that’s ultimately going to make sex less good for you?”

Q: How did you feel when you were talking to these boys?

Orenstein: I felt just deep compassion toward these boys who are in a system that is stripping them of humanity. They feel reduced as human beings and they feel reduced in their capacity to have relationships and they feel reduced in their sexual expression. And that is really hard to grapple with.

Q: Did any boys say that their parents had done a good job speaking with them about these tough topics?

Orenstein: If they did, it was usually their mom. But the more common discussion was a profound desire to have more from their dad. Real conversations with them about sex, about consent, about ethics, about relationships, and about their own mistakes. And I think that fathers resist doing that partly because nobody did it with them. One boy said, “My father’s not a jerk without a pulse. He’s more of a sigh and walk away kind of guy.”

Q: Do you have suggestions for fathers?

Orenstein: Many dads just didn’t learn how to connect. I think they have to try to be bigger than that. First, recognize that you don’t have to get it right the first time and you don’t have to be experts. Even if your own romantic history was kind of a shambles, you probably have something to say to your child about what you wish had happened or what you learned from that. If dads can make room for and allow their boys to express this other side of themselves, to be more fully human, then boys will do it because the fathers are there to support them.

Q: Give me an uplifting message to end with.

Orenstein: Boys made it really clear they wanted something different. So many boys wanted to be able to be more connected, to express vulnerability, to be able to feel and express love, to be able to have positive, consensual, ethical, good sexual experiences with a partner. And they wanted the guidance from adults in their lives, even when it makes them plug their ears and want to scream and run away. They wanted that guidance to get there. So I think that this moment in history that has been so upsetting in so many ways has given us this incredible opportunity to give our boys something that we have stolen from them systematically.