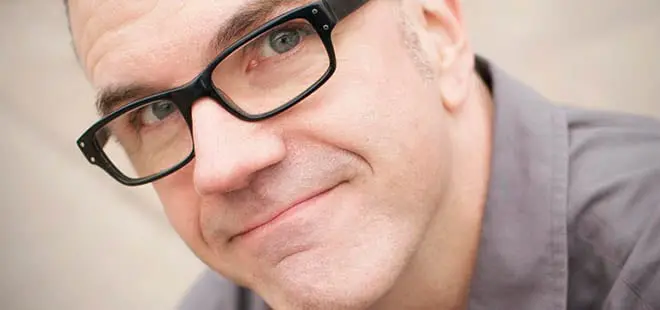

A self-proclaimed former “weird” teen, free-thinking entrepreneur Nancy Lublin is making her mark on the world through a series of socially minded ventures, from her founding of Dress for Success in 1996 to her current leadership at Crisis Text Line, an outreach platform for teens (and others) who need help. She’s also raising her own kids, ages 13 and 11—and as you might expect, she’s doing it in her own unique way.

Q: Can you walk me through how you got to where you are today professionally?

Lublin: I went to law school because I was a girl with a lot of opinions and ideas, so back then that meant law school. Then I got to law school and thought, This is terrible; this is not what I’m like at all. I started Dress for Success, dropped out of law school, and then I got bored because Dress for Success was doing well. I left and came to DoSomething.org [a social action site for young people], and then that was going well. Crisis Text Line grew out of that, and now Loris, [a for-profit subsidiary], has grown out of Crisis Text Line.

Really the only common thread between all of them—and it is only now clear to me looking back—is that every one of these things is about helping someone else live their best life.

Q: With your career path taking so many unexpected turns, how would you advise helping teens today find their own purpose or passion?

Lublin: One of the things that I’m trying to do is make sure that my kids see lots of different kinds of opportunities. I only saw doctors, dentists, lawyers, and teachers, so I thought those were my only options. So, just expose kids. Not, “Let’s try to figure out what your thing is, or what you’re good at, or what your passion is.” But show them that there are so many different tasks.

Q: What were you like as a teenager?

Lublin: If I was assigned an essay at school, everybody else would answer the question, and I would do something weird. I once wrote an essay where every single sentence ended with a question mark. The entire essay was just questions. We had to write about a world leader who we admired, so everybody wrote about Churchill or Margaret Thatcher, and I wrote about Attila the Hun. We had to write a book report on something, so I wrote a new last chapter of the book. Back then, the teachers and my parents were thinking, This kid is smart, but she’s a little weird. How is she going to support herself someday? Who is going to marry her? How is this going to turn out for her?

Q: What was it like to be a teen who didn’t conform?

Lublin: It’s emotionally hard to be the nail that sticks out. It’s lonely. No 13- or 15-year-old wants to be weird. You want to fit in. Most entrepreneurs that you talk to will say that they had a hard time growing up because they didn’t fit in and they really wanted to. I would have loved to have just been a cute junior varsity player and B student and just get by. I’m not wired that way. That’s why it’s so funny to me when people go to school to become an entrepreneur or say I really want to be an entrepreneur someday. Most people who are doing it didn’t pick this. It picked us. I don’t think I would be a great employee somewhere.

Q: Do you think your experience as an entrepreneur impacts your teenagers?

Lublin: Totally. Both my husband and I are entrepreneurs, so I’m convinced that my kids are going to grow up to be accountants or dentists. They’re going to rebel by taking some very stable, routine job. My daughter is a bit of a rule-follower, which is really funny to us. But they’ve definitely seen the roller coaster that is entrepreneurship. The only thing that’s harder than being an entrepreneur is loving one, so being the child of an entrepreneur, that’s really hard. You’re on the same roller coaster, but you have no control over it.

Q: How do you think your own parents contributed to who you are today?

Lublin: I like to say that I’m from a mixed marriage. One parent was a Democrat, and one was a Republican, and they were both politically very switched on, so every night we would have dinner and watch Walter Cronkite. We talked politics, and you were expected to have an opinion, and you better know what you were talking about. I was always a free thinker, because I would waver between them, politically, on different things, so I always had a mind of my own.

Q: How would you describe your own parenting style?

Lublin: I aspire to be a little more helicopter. We are consciously free-range parents and also unconsciously because my husband and I are just too busy. We’re working a lot. Monday they started code camp in New York City, and my husband and I both had meetings, so we said, “Here’s the address, have fun.” They had to get themselves to NYU.

Q: Do you have any family rules?

Lublin: We don’t allow video games in our house, so there’s a whole chunk of time that’s available. They’ll play it at their friends’ house, and it’s on their phones, but at home, we don’t have an Xbox, a Wii, or any of that stuff. I just don’t think that’s interesting. So, instead we have all kinds of weird family traditions.

Q: What are some of the weird traditions?

Lublin: On Father’s Day, we try to do as many ice cream shops as possible in one day. I think our record is six. On Friday night we have dinner together, and we go around the table and say our favorite moment of the week. We’ve watched every single episode of the original “MacGyver” as a family.

Q: Any other advice you have for parents of teenagers right now? You have your pulse on kids today through this texting hotline.

Lublin: I get asked a lot about the devices, and my husband actually turns off the kids’ apps after 8 p.m. and limits their app use on their phones, mostly because we think they become boring when they just look down at their phones all the time. We’d rather they talk to us.

I get parents who really believe that social media and the phone are what’s causing their kid’s depression, anxiety, or both. When my daughter looks at Instagram and there are a whole bunch of girls in a photo and they’re tagging each other and she’s not part of it, that’s painful. That stuff has always been painful. I remember that in the ’80s, too. But it would be too easy and too convenient to believe that there’s one thing that’s contributing to your kid’s challenges. Technology can be good, and it can be bad. Some of the stuff is painful, but you can also find stuff that’s really helpful, like the Calm app or the Headspace app, or Crisis Text Line.

Q: Should parents be suggesting Crisis Text Line to their kids?

Lublin: You could put a card about us on your refrigerator, but we don’t want to be the thing that parents tell their kids to use. We want to be the thing that kids tell each other to use, which is how we’ve grown so far—but we also want parents to know, we’re here for you, too. We’re here for everybody, all ages.

What is Crisis Text Line?

Nancy Lublin founded the non-profit Crisis Text Line in 2013 to provide free crisis intervention via text messaging. Since then, the hotline has exchanged more than 76 million messages. Anyone can text in with a problem they’re dealing with at any hour of the day. In the U.S., you can text CONNECT to 741741 (in Canada you can text 686868), and a trained counselor will do their best to help you calm down and problem-solve.

Anything you text Crisis Text Line is completely confidential, but they do collect anonymized data to improve the service they provide as well as help others handle crises. They’ve also decided to open up their technology so that others can use the text line. For example, you can text 4Hope to 741741 to get Ohio-specific resources, and Crisis Text Line provides the data to the state to help improve their own crisis handling. The National Eating Disorders Association lets you text NEDA to 741741 to get help.

One thing the company has learned from talking to so many teens is just how little sleep they all get. “One of the things we’ll ask at 4:00 in the morning when they’re texting us is, tell me, when is the last time you had a solid night’s sleep, and they’ll say last month, two weeks ago,” says Lublin. “It’s amazing how little sleep people are getting.”

While the original goal was to better cater to younger people who may be more comfortable asking for help on their phones, Crisis Text Line is open to all. “We’re here for everybody, all ages,” Lublin says. “It’s heartwarming: When parents text in and say, ‘I’m a father of two and I just can’t take it anymore,’ then if we save that person, we’re also saving his kids.”