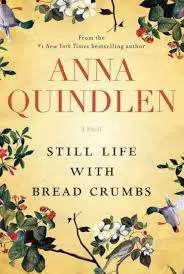

What can we say about Anna Quindlen that hasn’t been said many times before? A Pulitzer Prize-winning columnist for the New York Times and then Newsweek, she’s also the author of six fiction and eight non-fiction books including, most recently, the bestselling Still Life With Bread Crumbs. We’re big fans.

Anna Quidlen: Parenting, Writing, And More

Q: In the span of three years, you decide to leave the New York Times to raise your kids, but your career still worked out quite well. With all of the talk today around “leaning in,” how do you think women can find balance?

Quindlen: I didn’t leave the New York Times to raise my kids. I was already raising them when I was a columnist there. I left to become a novelist. But when a woman trades in a powerful job for one that is assumed to be less powerful, everyone assumes it’s because of her family. Debora Spar and Sheryl Sandberg both have something important to say to girls and women—and both of them are friends—but relying on only one would be like using only one news source to learn about the world. You have to read widely and deeply, and think hard, because there is no one-size-fits-all directive for how to live your life. If there was, I wouldn’t have left the Times in the first place.

Q: As a writer, how did you learn to deal with criticism?

Quindlen: The only critical voice that matters is your own. You have to learn when it’s speaking from certainty and when it’s speaking from insecurity. You also have to develop a transactional relationship with it. There’s a moment, at the end of the last draft of every book, when I read the manuscript aloud. That way I can hear all the clunks and stutterstops and run-on sentences.

Then when I’m done I say to myself, “Self, this is a good piece of work.” Embedding that sentiment in my psyche goes a long way toward keeping me sane. Of course, you have to have done the work first to make that a true, and truly felt, sentence.

Q: Have you built a thick enough skin so that you can ignore the negative criticism?

Quindlen: If you mean reviews, I haven’t read them for the last four books, even the good reviews. I wasn’t learning anything from them, really. My best friend vets them, and then she tells me who we hate. Works for me.

Q: You have referenced that people should try to live life like they have a terminal illness. Do you still believe that and have you been able to pass that philosophy on to your children?

Quindlen: Yep, more now than ever. I’m 62 years old, which means that I’ve lived a lot more of my past than I will get in the way of a future. I’m also at the age at which friends die, which only ought to redouble your determination to live your life with gusto. My kids don’t really get that in the way I did because they’ve never watched someone they love die by inches. But they’ve certainly heard the message enough.

Q: When your kids were teens, did they know that you were famous? How did it impact them?

Quindlen: When I asked them, they responded:

“You weren’t famous in a way that teenagers cared about (no offense). I’ve always been immensely proud of your accomplishments. But you never acted ‘famous,’ so it wasn’t something that registered much in my perception of you.”

It wasn’t the kind of fame that hugely impacted the life of a 16-year-old who was mostly interested in heavy metal. My friends weren’t giving me copies of Black and Blue to get signed.

Q: Do you have one big parenting mistake? What would you have done differently?

Quindlen: I think I was too focused sometimes on externals. Honestly, it didn’t really matter where my kids went to college. They were all smart, curious, creative. That wasn’t going to change. For two seasons I wouldn’t let them watch The Simpsons. I actually can’t remember why. Stuff like that. Now that they are 31, 29, 26, and fantastic, so much of that stuff around the margins just seems absurd.

Q: As you reflect on parenting, what are the three things that worked for you that you want to share with parents in the thick of teenagerdom?

Quindlen: There’s actually one primary thing: remember. Remember what it was like to be a teenager. Remember how everything that happened seemed so fraught and important, often because it was happening for the first time. Remember how friendships and crushes could throw you into a swivet, so that you won’t minimize it when it happens to the teenager in your house.

Remember how you were ruled by your hormones and moods. Don’t call your friends in a panic and say, “Oh my god, I think he/she is having sex/smoking pot/failing chemistry” unless you can genuinely say that you never had sex/smoked pot/failed a course when you were that age. Even if you can say you never did, remember the kids you knew who did those things and who went on to live rich and fulfilling lives.

Every time you deal with a 17-year-old, try to keep your own 17-year-old self front and center in your own mind. It made an enormous difference for me. Just remember.

Q: What do you wish you hadn’t worried about?

Quindlen: The SATs.

Q: What do you think parents today worry about that they shouldn’t?

Quindlen: The SATs.

Q: What do you think parents today should worry about?

Quindlen: Henry James once wrote, “Three things in human life are important: the first is to be kind, the second is to be kind, and the third is to be kind.” If your kids grow up learning and living that, you’ve been a success as a parent.

Q: Can you share a moment you are proud of as a parent?

Quindlen: It doesn’t work like that. You think it’s going to be graduations, or weddings, or curtain calls. But it’s really that moment when you look around the dinner table, and they’re all talking about something interesting and important, and one of them makes a trenchant observation, and another makes a great joke, and you think to yourself, I made three great humans.