When I had just turned 13 years old, I had a wacky, fun-loving science teacher. He was eccentric and quirky and made lots of jokes, and everybody loved him. Everybody except me. Because he was mean to me.

It’s 25 years later, and I can still feel the pencils he threw at me. I can still remember the sound of his voice, hitching up in mockery when he asked me if I was crying.

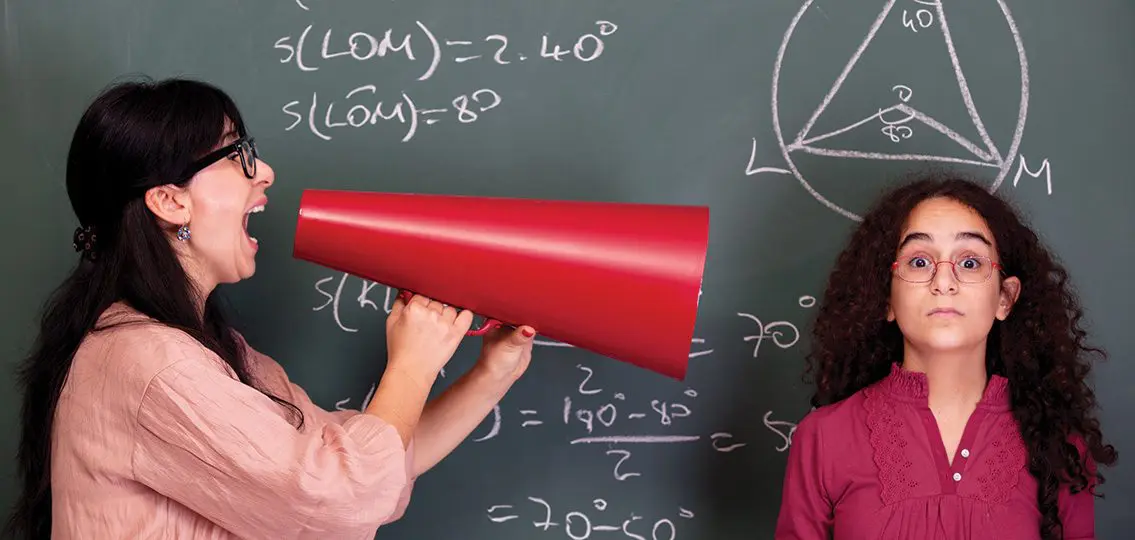

In recent years, school systems have come a long way in how they educate about and protect against bullying. But most of those resources go toward peer-to-peer harassment. Teacher-student bullying is harder to pin down because there are so many variables at play, including teachers who are overworked, overburdened, and simply doing their best while being given very little in return, says Alan Kazdin, a professor of psychology and child psychiatry at Yale University.

“Teachers get little appreciation for what they do. They have parents on their back, kids on their back. Their classroom sizes are larger, their test scores have to stay up. Teachers are besieged,” Kazdin says. “And we’re still dealing with humans. We all have pettiness, insecurities, and such. Sometimes it’s a bad mix.”

Teachers Bullying Students: What’s the Problem?

In a 2018 survey conducted by researchers at Northern Michigan University, 86% of teachers said they currently knew of at least one teacher in their school who bullied students, when bullying was defined as “a pattern of conduct, rooted in a power differential, that threatens, harms, humiliates, induces fear, or causes students substantial emotional distress.”

In the survey, teachers said their coworkers most often targeted low-achieving students and those with behavioral disorders, followed by students of color and LGBTQ students. “Bullying stems from any sort of difference,” Kazdin says. “Being too thin, too fat, too tall, mixed race, or having sexual identity issues different from the majority.”

Stopping teacher bullying is just as important as handling peer-to-peer bullying because the power differential changes the dynamic, explains Kazdin, who is also the director of the Yale Parenting Center. “In these cases, you have an adult whose words come with more crushing authority,” Kazdin says. “Kids can say a peer is in a bad mood or teasing, but they can’t discount authority figures so easily.”

What’s the Teacher’s Goal?

Many times, teachers mean well. Embarrassment is part of their toolbox for motivation.

“Bullying typically has a small audience, or maybe no audience,” Kazdin says. “But in teacher-student bullying, the teacher is standing in front of the class, which adds humiliation in front of peers.”

Recently, my 11-year-old daughter hadn’t been completing her work. The teacher offered to say loudly in class that she would be looking over my daughter’s shoulder during class for these assignments. I quickly said, “No, thank you,” and the teacher didn’t do that. My child would have felt betrayed and belittled, and she certainly wouldn’t want to do the work. The teacher may have been trying to motivate, but being humiliated in front of her classmates would decimate my daughter’s self-esteem, whether it was intentional bullying or not.

What Should Parents Do?

In my daughter’s case, speaking with the teacher solved the problem before it even began. Talking with the teacher is often an effective first move, says Emilie Blanton, a Kentucky high school teacher trained in restorative practices, a proactive means of promoting and repairing relationships. “Ask to meet or call. Say, ‘My child is saying that this is happening, and I would like to discuss the matter with you.’”

Make sure you go in with an open mind, ready to listen to another account of what is happening in the classroom. But be discerning—just because one person in the room is an adult doesn’t mean their story is automatically more reliable.

Sometimes there are misunderstandings that can be cleared up by a parent-teacher conversation. But even if it’s more than that, talking with the teacher is often a necessary first step that documents the need for additional parent action, says Blanton.

That next step, she says, would be contacting an administrator or the principal. That’s especially if the initial meeting results in exacerbated bullying behavior. The last resort, she says, would be changing your child’s class if a meeting doesn’t improve the dynamic.

Kazdin cautions that one-on-one meetings with the teacher or principal might not get the job done in some schools. “A parent going to the principal or to the teacher is the least effective way to go about it,” he says. “The parent goes in, and the thought is, ‘Oh, I see where your son gets it.’”

Kazdin says the most effective route may be gathering a group of concerned parents and working with the school board to make change.

Schools can respond with workshops, training, funding, and maybe even more support for teachers, many of whom are frustrated and overwhelmed.

The main goal is to create a safe and transformative learning environment for your kid. Says Kazdin, “We want kids to love learning, not loathe it.”