What makes a person influential? Is it their actions, their friendship, their life? For me, Andrei Philip Lehman didn’t influence me through his life, but unfortunately, through his death.

Andrei, known as Andy, was a senior at Notre Dame Cathedral Latin when I was a sophomore. Andy was a genius, effortlessly completing the most advanced courses in high school. Described by his father as “a true renaissance man,” Andy was especially brilliant in mathematics, able to compute complex equations in his head. A winner of the National Merit Scholarship, Andy was granted early acceptance to many prestigious colleges.

But my classmates and I saw Andy as too smart to have social value. We saw him as a geek and an easy target. We wondered aloud why he still rode the school bus as a senior. We taunted him about his weight, calling him “polar bear.” Because that moniker stuck, we never even knew his real name.

For most of the year, I was the ringleader of this horrible circus. I bullied him constantly.

September 19, 2006, began as a typical day. I took my seat with the rest of my business class and noticed that the usually punctual Mrs. McNulty was late. When she finally arrived, she was crying. As the students exchanged looks of wonder, morning announcements came over the loudspeaker. Principal Waler instructed us to pay close attention to an important announcement: Andy Lehman had passed away.

Silence filled the room as I wondered to myself, “Who was Andy Lehman?” The name was familiar, but I couldn’t conjure up a face. Students pouring into the halls exchanged nervous looks; some crying, some, like me, staring blankly into the distance. A close friend of mine, Colleen Heffner, ran up to me. Mascara and eyeliner ran down her face as she cried and embraced me. She could only manage a few words: “It’s Polar Bear.”

During second period, Mr. Waler addressed the student body. With great pain and sadness, he explained that “Last night, at 8:38 p.m., Andy Lehman died by suicide.”

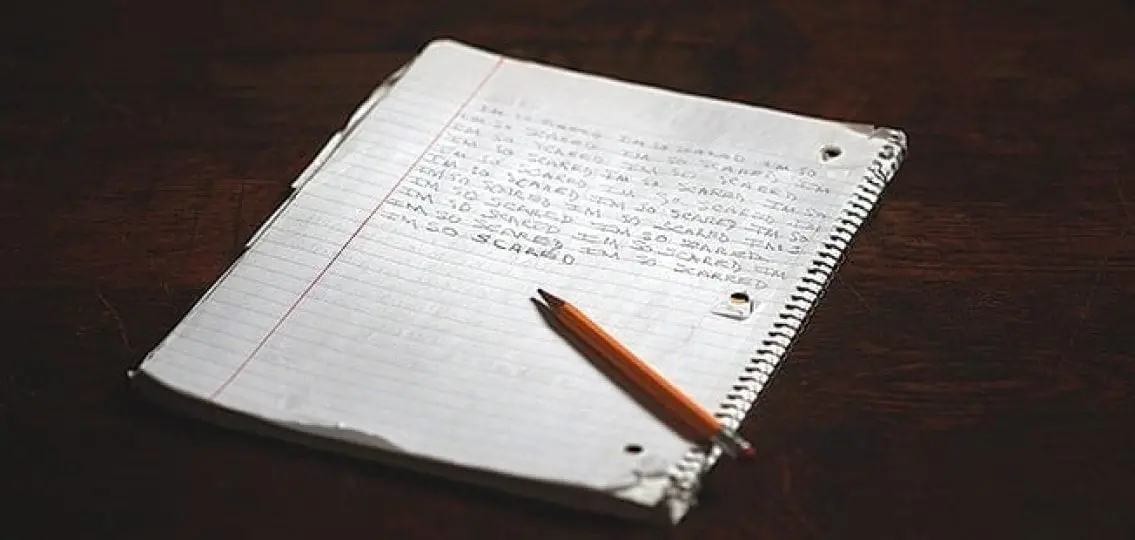

I don’t remember much after that, as a tingling feeling of guilty shame ran up my spine and through my arms and sweaty hands. I felt solely responsible and guilty for Andy’s death—he was bullied to suicide. Mr. Waler continued to speak as I sat frozen at my desk, unable to move or look anyone else in the eye. That moment will replay in my mind forever.

Three months after Andy’s death, I shuffled downstairs and stepped into the kitchen to eat breakfast. Glancing at the News-Herald, a headline caught my eye: “Dad Pushes for Depression Awareness.” The article began: “On Sept. 18, one of the area’s brightest teenagers took his own life without warning. Now, three months after that tragic event, his father is trying to piece together what went wrong and looking for ways to help prevent such tragedies from occurring again.”

In that instant, I knew that I needed to pay my respects to the man who lost his only son to suicide. I needed to tell my responsibility in bullying his son.

Sadly, had I not seen that article, I might never have realized that I needed to make things right.

That night, I walked one street north from my house to Mr. Lehman’s house. I had no pre-written apology, no mental notes of what to say to a grieving father. I didn’t know what to expect, but I hoped that some piece of my guilt might be wiped away.

Five minutes later, I sat in the Lehmans’ kitchen, and told the story that had been bottled up inside of me. Three hours later, I had learned so much about Andy. He and I had similarities; we had both seriously considered suicide and both suffered from teenage depression. I learned that while many factors contributed to his suicide, our bullying, combined with his deep depression, undeniably led him to act.

I couldn’t absorb everything that night; it took days to sink in. Mr. Lehman had welcomed me into his home and appreciated my sharing a larger piece of the puzzle of his son’s life. There was no anger on his part—only love.

Since that day, my mission has been preventing tragedies like Andy’s.

I have the honor of working with Mr. Lehman and the Suicide Prevention Education Alliance, as a certified speaker and teacher of their core curriculum throughout the Cleveland area. I strive to fulfill this mission as well as I can, for Andy’s sake.

The biggest lesson I learned from Andy is that our words always matter and they can hurt more than physical pain. I knew nothing about Andy, and I had neither the common courtesy to care, nor the compassion to stop taunting him. I will live with that burden for the rest of my life. When Andy died, he became a part of me, ingrained in my soul forever. His legacy lives on through me, as I work to prevent teen suicide.