“I’m sorry. I don’t know why this is happening,” I sobbed in front of the bat mitzvah tutor as we prepared for my daughter’s ritual transition into Jewish adulthood.

My teenager’s eyes widened. “Mom, stop.”

But I couldn’t stop crying. As an Italian Catholic, I felt left out. I envisioned another “challah moment,” like the one at my interfaith wedding when I forgot to tell the catering hall to provide the sacred loaf for the Hamotzi, a prayer over bread. I’d felt all eyes on me, the non-Jewish bride.

“You never know when it’ll hit you,” the instructor explained. She didn’t know that my daughter had already sprouted four inches above my five-foot frame, and how just that height difference felt like she grew away from me. Now my daughter was preparing to become a Jewish woman, something I’d never be because I chose not to convert. I feared we’d be unable to connect on this milestone.

“Mom, how should I start my D’var Torah?” my firstborn asked, breaking the silence as we drove home.

“The part where you explain your Torah portion? Right?”

She sighed, and as I glanced at her, I saw she rolled her eyes. “Forget it. I’ll ask Dad.”

Throughout our lives, spirituality was a strong force for both my husband and me.

I attended Catholic school, and he went on a teen tour to Israel. We both believed in honesty and charity. We’d considered raising our children with both religions, but felt it was too abstract. My husband conceded that if I could promise to raise our children in Reform Judaism, it would be enough to get his Conservative parents’ blessing.

Still, I wouldn’t convert. Although drawn to my college sweetheart’s gorgeous green eyes and Judaism’s tenet to repair the world, I couldn’t entirely relinquish my Catholicism. I was madly in love with him, though, and so I agreed that Judaism and Christianity were simply different religions leading to the same God. I assured myself I’d be content passing down my holiday traditions without teaching my kids the Christian meaning. I wanted to provide my offspring with moral consistency. Judaism’s principled teachings and position as the root of Christianity seemed like a solid choice for our children.

But later, as I delivered my daughter biweekly to and from the synagogue for intense bat mitzvah ceremony preparations over the course of a few months, I realized I didn’t know what they were teaching her. I didn’t know anything about Jewish traditions. It felt like she was being inducted into a sorority that I wasn’t allowed to join since I was never called to the bimah myself. When she came home from those Hebrew tutoring sessions vocalizing phrases that were familiar only to my spouse, I felt small pangs, like God was telling me I’d alienated myself from my offspring.

So then I covered up my anxiety with a desire to perfect the celebration following the event. I’d show her the utmost support and do it right. At least she couldn’t say that her awkward mom failed at planning a meaningful gala. I grilled my close friends about what the ritual entailed. The party planner claimed I was the best Bat Mitzvah mom and promised to create an incredible bash complete with challah for the Hamotzi.

Still, it felt like something was missing.

Then, our rabbi asked, “Would you like to make an aliya?” My heart throbbed with excitement when he invited me to recite this Hebrew blessing, considered a high honor.

“You should do it, Mom,” my daughter said.

“Yes,” I practically shouted, jumping at the chance to finally take part in my firstborn’s ceremony.

A week before the service, I booked the photographer for extra hours so I could have every moment preserved. I studied the prayer ad nauseam, yet as soon as I gained fluency and confidence, I contracted strep and the flu.

Quarantined from the rest of my clan in my room, I lay in bed, unable to perform last-minute tasks like presenting babkas to the out-of-town guests. I saddled my father-in-law with the cakes, trusted my husband would pull together our two younger children’s outfits, and added my raspy voice over to the video montage.

“Send me the Cantor’s recording of the aliya prayer. I deleted it,” I texted my daughter as I tried to mimic the proper cadence of the foreign scripture.

“Mom, stop making a big deal. I memorized a whole Torah portion.”

She had no idea how big of a deal the prayer was to me. If I could recite it perfectly, then we’d be connected.

I recovered from my sickness just in time to stand up before the congregation with my girl. The guests smiled at me as I read the first phrase of the sequence. And then paused because I lost my place. A nervous chuckle escaped from my mouth, and then I proceeded to flub the foreign words I’d studied so hard to perfect. Heat rose around my ears. It was another “challah moment,” just like at my wedding. I fumbled my way through the rest of the passage and sat down.

Then it was my daughter’s turn at the bimah.

She chanted the aliya perfectly, then said in English, “My Torah portion is named for Jethro, a Midianite priest, a different religion.” She explained that it was about the ancient interfaith marriage of Moses to Jethro’s daughter. The Torah was read in synagogue three times per week, in order. The chances of my daughter’s Bat Mitzvah date landing on this pertinent interfaith passage were slim. Yet, here we were. I attributed this happenstance to our maker’s divine intervention. I made the right choice to raise my children outside of my faith.

“Though she would have never thought that she’d be planning around her kid becoming a bat mitzvah, my mom has been a role model for me. From the Jethro in my life, my Italian mama, I’ve learned to embrace all different kinds of people. She’s taught me that though religion is something that usually defines us, it doesn’t have to separate us,” my sweet girl said, then she smiled in my direction.

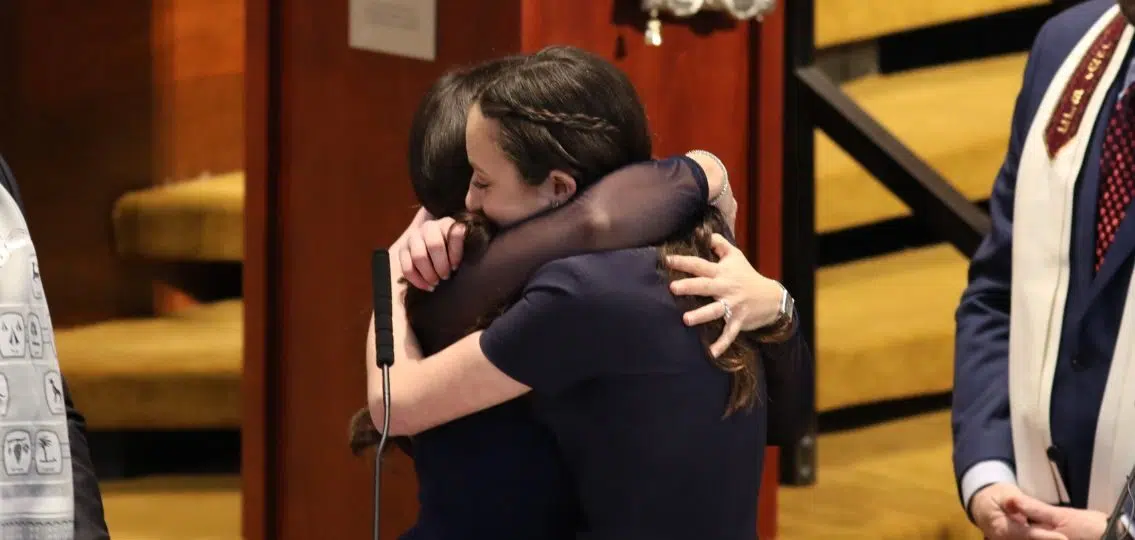

I hugged her so tight, the Rabbi had to pry us apart.