What happens when a teen feels one way about a particular issue or problem and the parent has a very different take? At Your Teen, we understand that sometimes you need to look at a problem from multiple perspectives. It can also be helpful to hear from a neutral third party. That’s when we bring in a parenting expert to provide the practical advice you need to bridge the divide and guide you in the right direction. In this piece, a mother wants to push her son out of his comfort zone and her son has different ideas. An expert provides her feedback on how important it is to find the right level of “scaffolding.”

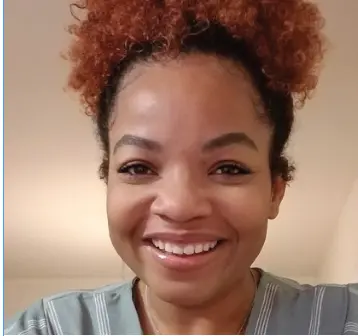

PARENT | Kelly Glass

The teenage years, however, have changed much of that.

As Kaleb became more aware of his differences, his anxiety became more prevalent. This new territory called high school has also proved to be a challenge.

Each school dance and social opportunity sparked my excitement, and I planned relentlessly—taking him shopping and talking up the opportunity for him to engage with peers. The button-up shirts were itchy, he said, and the pants weren’t comfortable to move in. “This is what young men wear to dances,” I would say.

Eager to see him in action, I chaperoned homecoming, only to find him sitting down watching videos on his phone. “How was the dance?” I asked on the car ride home.

“Good.”

I’d press: “Did you have fun?”

“Yes,” he’d say.

I dedicated years of my life to coaching him on social skills. When I see him in social situations not using the tools I’ve given him, I can’t help but worry. I cannot accept that he has had a good time, even if he insists, when I know he’s been on his phone most of the night. While I encourage him to join in and make genuine friendships, I try to keep in mind that reading social cues and facial expressions and understanding figures of speech and certain humor don’t come naturally to him. I can’t imagine how much effort it takes him to interact in such prescribed ways.

I also know that he desires friendships, and I want that for him, too, but what that looks like to him is different.

When I was a freshman in high school, I wanted to go to the movies and hang out and talk after. I wanted to be out of the house. He, however, is happy to have someone over, greet them, and then dive face-first into solitary screen time.

I can’t help but wonder if the time I spent coaching him out of carrying on lengthy one-way conversations about a singular topic backfired—maybe much of my prodding has. Or, maybe it was my pushing that encouraged him to leave his comfort zone just a little bit and participate in the plays, for example, that he now looks forward to. As careful as I think I am, though, I imagine it only takes one time pushing him too far out of his comfort zone to hurt his confidence as well as our relationship.

Kelly Glass is the Executive Editor for Back Parenting at Parents.com. She is a writer whose work focuses on the intersections of parenting and diversity and inclusion.

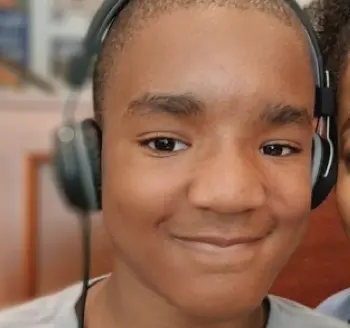

TEEN | Kaleb Curry

I don’t always remember. It can be easier for me to be on my phone, but I’m not always on it.

Usually I just wave at people instead of using my words. I feel nervous when it comes to meeting new people. I don’t know why. Sometimes I use animal noises or pretend to be a monster. Friends laugh when I do that.

When I don’t like to say “Hi,” some people don’t think I’m a friend.

I’m a silent type of person. When I don’t want to be talked to, I like to stick to being quiet. That’s not the only thing that I like. I like acting in the plays my mom puts me in. I get to be someone else. But I don’t always like saying my lines.

When I go to the library after school, I see other kids sit on the floor, but my mom asked me not to do that. They think it’s cool, though, so I want to do it anyway. If I follow all the rules my mom says, the other kids will think I’m not cool. I talk about dinosaurs and show the kids images of them on my phone.

Mom came to homecoming with me, but I didn’t feel like dancing. It was loud and dark, and I had feelings that made me not want to talk to anybody. Spring Fling was better. Mom didn’t come to that one. I danced a little, and I made a new friend.

Sometimes I feel better when no one is watching.

Kaleb Curry is a freshman in high school who loves animals, including his schnauzer mix Winston, as well as studying dinosaur species.

EXPERT | Jeanette Sawyer Cohen

Kaleb, like most teenagers, is aware that he is no longer a little kid, but he’s also not quite an adult. That in-between place is a hard place to live. Kaleb’s examples show that he is seeking more independence from his parents and looking to fit in with his peer group. He describes wanting to sit on the floor of the library because that is what the other kids his age are doing. He wants to follow the rules of his peer group (“sitting on the floor is cool”), not the rules of his mom (“sitting on the floor is not allowed”).

Kaleb mentioned some other rules, like no hugging, use your words, and give personal space. Following these rules will help Kaleb socially, but it sounds like breaking the rule about sitting on the floor will also help him socially.

Kaleb and his mom may want to have a conversation about how following some rules will help with friendships, while being flexible about some other rules may also help with friendships.

Similarly, Kaleb described having a good time at the Spring Fling that his mom did not attend. He danced and made a friend. In contrast, when she attended homecoming, he did not participate. It sounds like he may feel more comfortable venturing out of his comfort zone when his mom is not around, maybe because there are fewer relationships to navigate at once.

Kaleb’s mom raises an important question about whether her pushing him out of his comfort zone is helpful or hurtful. It depends. Psychologist Lev Vygotsky demonstrated that kids learn best when adults push them just above the level of skill they have mastered independently, to the next level where they can perform the skill with help. Later, psychologist Jerome Bruner coined the term “scaffolding” to describe how adults can provide support to help students learn and grow.

Kelly and Kaleb describe a good example of successful scaffolding: Kaleb is interested in and enjoys acting, and his mom provides opportunities where he can build on that interest. Acting may be a good way for Kaleb to practice expressing himself verbally. Even though he doesn’t always like saying his lines, acting sounds like an area where he can tolerate being pushed, because he likes pretending to be someone else, so he doesn’t experience it as being pushed too far.

A good formula for scaffolding in general, and especially for those with autism, is to start with something they’re interested in and then expand from there.

Individuals with autism spectrum disorder often have intense sensory experiences. Kaleb described homecoming as loud and dark, and his mom mentioned that he found the dress clothes she bought him to be itchy and uncomfortable. When Kaleb is physically comfortable, he may be able to be pushed or to push himself to try something that is anxiety-provoking or difficult, like having conversations or participating in a dance. But when he is asked to do something challenging like that and he is distracted or overwhelmed by sensory input, that is one challenge too many! Kaleb and his mom may want to discuss ways to minimize physical discomfort in different situations so that he can focus on socializing.

Kaleb and his mom both share the same goal of helping him make and sustain meaningful friendships. To make progress with this goal, they will both need to make some compromises and, most importantly, keep the conversation going.