About two years ago, my son, who is Mexican-American, came home and told me about two elderly white men in a golf cart in our golf community, who approached him and his three best friends, who are African-American. The men pulled over as the boys were walking to the lake in our neighborhood and said, “You boys need to go home to your own neighborhood.”

The boys all live in our neighborhood.

Fortunately for those senior citizens, my son could not give me a description beyond “older white men,” or I would have been on their doorsteps.

“Walking While Brown”

I try to tell my son that even “walking while brown” is an issue in this country. I wish it weren’t. But the fact is I doubt any parent of a child who is a minority has not had such discussions with their child. As my best male friend, an African-American journalist, told me, “Welcome to ‘the talk.’”

I write this from a place of absolute privilege. I am white—with all that entails. No one is coming up to me and saying, “Go home to your own neighborhood.”

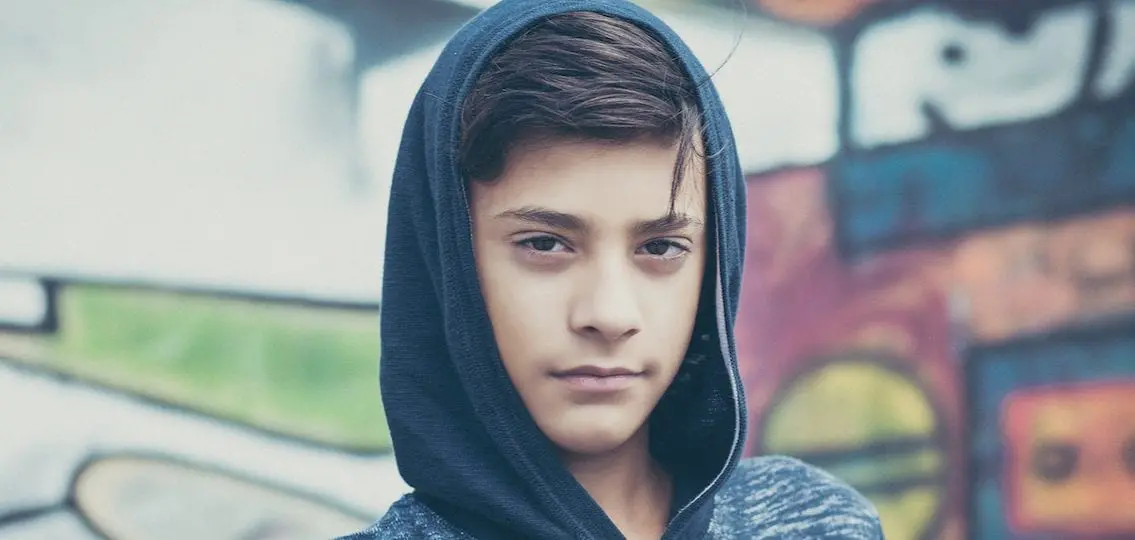

However, my son has decided to grow his hair long—and while he passed as white for years, he is now quite obviously Latinx. And I worry about his safety, and the safety of his friends, because kids think they are invincible.

A few weeks ago, my son had a sleepover with the same pals.

Not at my house, where I generally do not sleep if they have sleepovers so I can keep an eye on things. They got the bright idea to sneak out at 4 a.m. to walk to a convenience store for candy.

And they were stopped by a cop, who was very nice. He basically said what I would have:. “What the heck are you doing out at four in the morning?”

As a mom, I know my kid is not a trouble-maker, but I do expect teens to do stupid, but relatively harmless, stuff. So I shrugged at sneaking out to buy candy.

What If?

What I did not shrug at was all the ways that could have gone sideways.

He and his friends are 14 and 15—big teen boys.

What if someone saw them and decided they looked dangerous?

What if someone did not like their skin color and decided to call 911?

What if the police officer thought one of them had an attitude, instead of their usual “Yes, ma’am’s” and “Yes, sirs” (I know these boys)?

What if one of them reached innocently into his pocket and pulled out his cellphone?

The nice officer asked my son’s name, which is one of the most common Mexican surnames in the world. What if he wondered if my son was a legal citizen and decided to put him into the back of his cruiser until I could come to the station with his birth certificate? (Which considering how disorganized I am, could be a problem.)

My mind went to so many scenarios, none of them, I will be honest, positive in any way.

The Talk

We do that. Moms and dads. We know enough about life that we know that trouble can happen in the blink of an eye, especially in the middle of the night.

So my long-haired boy and I had a discussion. About what it means to be a Latino boy right now. About what it means when police or others encounter brown boys. About what it means to encounter a police officer. About how to stay safe. About, frankly, not doing dumb stuff—like walking around in the middle of the night.

But I know I can only cram so much into his brain. Because in reality, most teens think nothing bad is going to happen to them, especially if they are not looking for trouble.

Our conversation is not the first about such things. It won’t be our last. But I just want what all parents want. For my son to be seen as a person, not a race or ethnicity.

He is my boy. My beautiful Mexican-American boy.

And I have to hope and pray that he stays safe through the teen years. And that he understands how fragile life is. And I have to hope he can understand, even as the teen years are for testing boundaries and doing stupid stuff, that he needs to stay safe.

Because none of us is invincible.