You know your child is bright. Over the years, you’ve witnessed the proof firsthand: the toddler who could masterfully complete their favorite wooden puzzle in less time than it took for you to retrieve their chucked sippy cup; the six-year-old who negotiated a bedtime extension with the fervor and elocution of a senior-level attorney; the nine-year-old whose creative LEGO builds could best be described as engineering marvels.

The answer isn’t one-size-fits-all, but learning differences are much more common than you’d think. One in 5 students have them—yet many don’t receive proper diagnoses, says licensed clinical psychologist Dr. Kelly Christian of Lawrence School.

According to Christian, the signs can vary, but frustration is a common theme. A student with an unidentified learning difference often becomes easily discouraged and might even try to avoid a particular subject like reading, writing, or math altogether. They could also be disorganized, losing assignments and absentmindedly forgetting to study for upcoming tests. For some, homework time is a battle that ends in tears. If you see this in your child, or if their academic performance simply has you scratching your head, it’s time to dig deeper.

Diagnosis is Important

Most students with learning differences begin to show signs around first grade, says Christian. But only a small percentage are actually identified this early. She regularly sees teens who were never properly diagnosed—many of whom had even been described as lazy.

| [adrotate banner=”230″] |

When school personnel or a psychologist evaluates a child for learning differences, they use standardized tests based on national norms to look for gaps between the child’s intelligence quotient and their academic abilities. If a child has a very high IQ, for example, they should be reading, comprehending, and able to complete math problems at a level that is comparable.

Christian identified four of the most common types of learning differences and their prominent symptoms:

Dyslexia (Learning Disorder in Reading): In teenagers, they tire quickly when reading for any significant length of time. They also read slowly and tend to over rely on their knowledge base or experience to make inferences about what they read. Parents might also notice their teen struggling with spelling, even if in the past they were able to memorize words and score well on elementary school spelling tests.

Dysgraphia (Learning Disorder in Written Expression): Adolescents with dysgraphia may have a lot to say about a particular topic, but when they try to write it down, they are only able to produce basic sentences that don’t match the elaborate stories they tell. Parents might hear their teen complain about the physical aspect of writing.

Dyscalculia (Learning Disorder in Mathematics): Teens with dyscalculia often lack number sense and it is hard for them to answer questions that involve money or time. They may not be able to comprehend what an hour is, or ideas like “less versus more.” Practicing or drilling their math skills doesn’t seem to help.

ADHD (Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder): ADHD is a disorder of inhibition. Regardless of whether it is the inattentive, hyperactive, or combined type, adolescents will all struggle to focus their attention, manage time, and get organized. Socially, they might also struggle to foster relationships with peers due to impulsive behaviors, challenges managing emotions, and difficulties keeping up in conversation.

What Can Parents Do to Help?

If you suspect your child may have a learning difference, start by speaking to the staff at their school. Your pediatrician may also have suggestions for psychologists or testing centers in your area. Simply put, says Christian, if you don’t get a diagnosis for your child’s learning difference, they won’t get the proper help and resources they need.

Jack’s story is the perfect illustration of this. He had trouble reading in early elementary school, says his mom, Kassie. Two summers of tutoring helped, but only a little. It wasn’t until he was formally diagnosed with dyslexia that he began to get the help he needed.

Research shows that with a specialized curriculum and instructional approach, students with learning differences can close their gaps in achievement. And although learning differences are found in every classroom, many educators don’t have the training and expertise to help a student in need. “Our tutoring continued—but we found a tutor that was specifically trained in how to tutor someone with dyslexia,” Kassie recalls. “Jack’s progress was instantly recognizable.”

Trust Your Gut

“Jack tested in the acceptable norms throughout his early schooling years, and plenty of people said his development was normal—that one day it would all click,” Kassie says. Unfortunately, that wasn’t the case. She continues to be grateful she trusted her gut and had her son evaluated so he could receive the interventions and accommodations he needed to thrive.

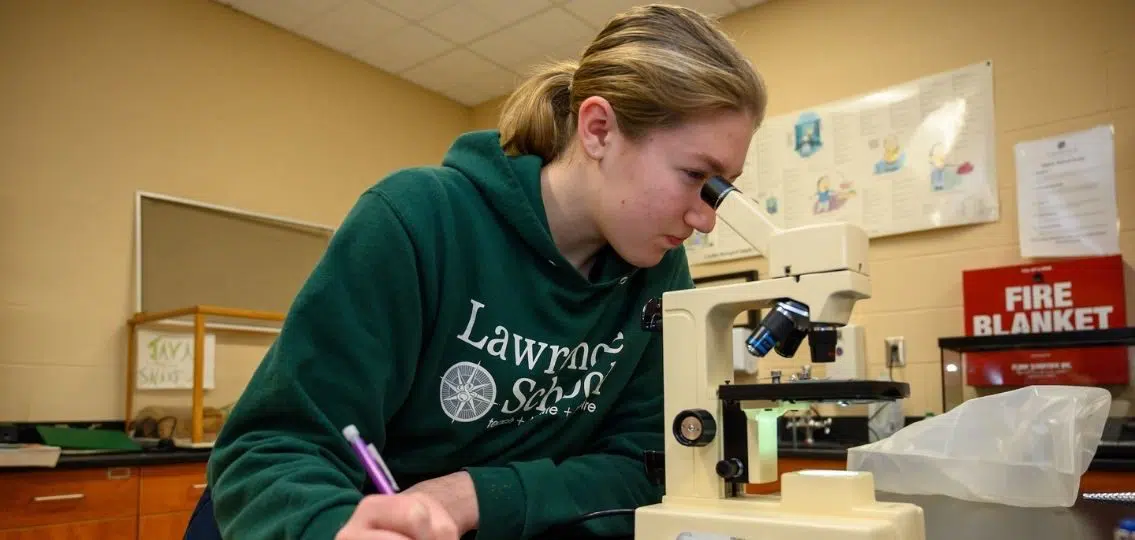

Jack is now an eighth grader at Lawrence School, where the college-preparatory curriculum is custom designed for students with learning differences. Through the school’s Orton-Gillingham based, multisensory approach, Jack has unlocked the code he needed to learn to read. “Now he’s also a book lover,” his mom shares.

Kassie’s advice to parents seeking help with a potential learning difference is this: “Follow your heart. If you feel like something isn’t quite right, it probably isn’t.”