According to Marc Brackett, Ph.D., there are thousands of words in the English language that describe emotions. “Sadly, most of us fall back on a few: Fine, Okay, or blah.”

Brackett, Founding Director of the Yale Center for Emotional Intelligence and Professor in the Child Study Center at Yale University, and author of Permission to Feel: Unlocking the Power of Emotions to Help Our Kids, Ourselves, and Our Society Thrive, believes that it is parents’ “moral obligation to make sure that children have the language to describe their emotions.”

“The goal of emotional intelligence isn’t to get rid of emotions. It’s to embrace and experience them as they are and learn strategies for how to manage them so they don’t have power over you, explains Brackett.

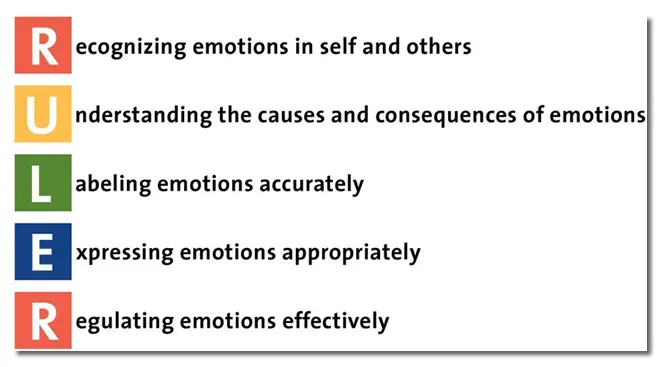

On a mission to be intentional about teaching social and emotional skills to kids- both in and out of school – Brackett’s evidence-based approach goes by the acronym RULER:

How can parents help their children become “compassionate emotion scientists”?

How to Teach Emotional Intelligence

Here’s what Brackett recommends:

1. Give yourself and your kids permission to feel all the emotions

Many people feel like they don’t have permission to do so. Brackett acknowledges that there many people, men in particular, have “meta emotions.” They have worry or shame about the feelings that they are feeling because they don’t want to be perceived as weak for feeling anxious or stressed. Students also are unwilling to talk about unpleasant feelings. Bracket points out, though, that “It’s not about being happy all the time, which I think is terribly misguided.”

2. Be in a learning mode with your kids.

Let’s say that your child comes home, throws down their backpack, and shouts, “I hate you.” You’d be temped to say that they are frustrated. But Brackett explains that by making that assumption, we are performing an “attribution error” and judging the behavior instead of the emotion. This is when we have to suppress our own reactions and ask, “Hey. What’s going on?” That way you can find out the emotion that led to the behavior you witnessed. (Of course, later, there is an opportunity to discuss how to manage that emotion in a better way).

3. Normalize talking about feelings

Kids need to see their parents talking about emotions and sharing how they feel. Saying, “I had a tough day at work.” Doing so makes them feel more comfortable opening up about unpleasant things. At the same time, when we ask our children how they’re feeling, we need to be willing to take the time and listen what they have to say.

4. Participate in emotional regulation strategies together.

Brackett shares how his family has begun taking walks together as a way to decompress. He also reminds us that “there is no wrong strategy. It’s not your job to help your kid use your strategies but to help them discover ones that work for them and enable them to maintain positive relationships.”

5. Schedule down time as a family

The do-nothing time is so important. “That’s when some of the best things happen. Your guard is down, you’re relaxed; when you’re under pressure, your brain is not in creative mode. It doesn’t require money. Just take the time to go for a walk or play a game. Do something that’s not cognitive and more relational,” suggest Brackett.