As much as we’d like to say it isn’t so, teen suicide is something that we need to know about and talk about. Following are the powerful and brave reflections of a mother and her teenage daughter who attempted suicide. Their goal in sharing their stories is suicide prevention. To that end, we’ve also included some advice from an expert.

TEEN | Stacy Brief

TEEN | Stacy Brief

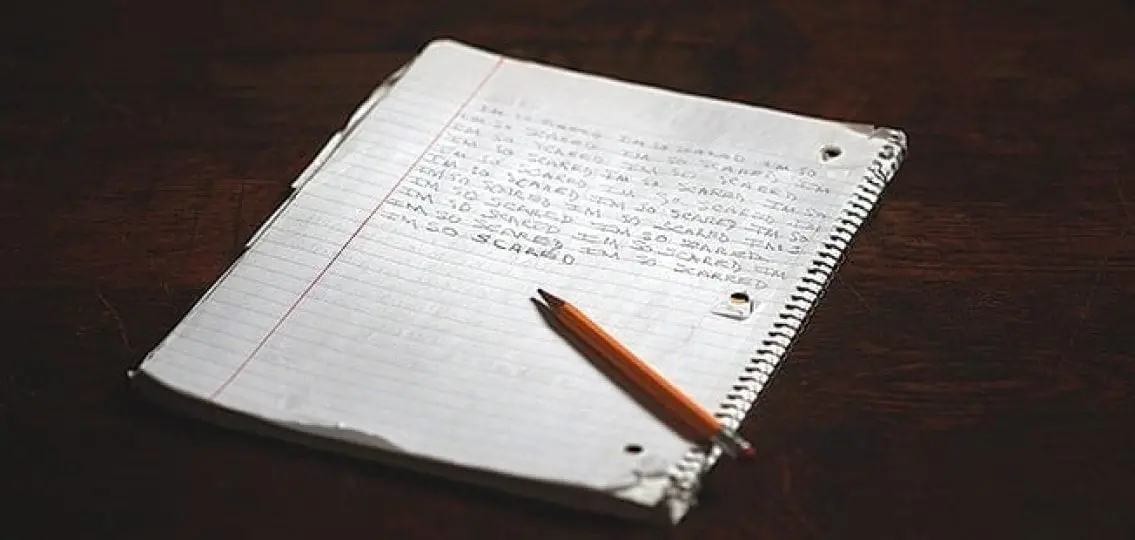

It’s hard for people to imagine. Hard for people to understand. Hard for people to accept. When someone hurts themselves or looks to end their own life, it scares people. But it is hard for that suicidal person to understand, too—and it scares them just as much.

A suicide attempt is rarely a spontaneous decision. It took years of feeling as though I did not belong or fit in. I was harshly judging myself, and I felt socially ostracized and bullied. I developed severe feelings of shame and hatred toward myself before the suicidal ideation began.

I desperately wanted to be accepted by a group of people who were constantly pushing me out and reminding me I was not good enough. The constant agonizing emotional pain that I was feeling—and that I did not know how to articulate and express—spiraled into wanting to die.

There were times when I had an elaborate plan. I knew how, where, and when I was going to go through with taking my life. At times like these, I was at the most danger to myself. I was the most desperate and needed the most intervention.

Sometimes, it was more of an abstract wish not to exist—wanting to disappear and not face the pain or struggles I had been facing every day. When feeling like this, I did not necessarily wish that I was dead. But wanting to disappear still posed a threat and left me on a path where I would want to take my life.

And at other times—less severe times—my desire to die came through in reckless behaviors. Feeling suicidal can be as simple as crossing the street without looking, reckless driving, or drug use. I remember walking across a main road at a green light, not caring what happened to me.

As I started to feel more suicidal, I began to make cries for help.

I was self-harming; I isolated from those who cared about me; I slept irregularly; and I made small comments that often went unnoticed about “not being here” for the future. These were signals I was sending that I was hurting and that I couldn’t handle life anymore.

At the same time, these signals were hard for others to notice because I did my best not to reveal what was going on internally. I maintained a 4.0 GPA, played sports, and smiled. People had an idea of what a suicidal teen looked like, and I did not fit that mold.

Now, being at a point in my life where I can look back with insight and reflection, I can tell my parents how to help me moving forward, and I can tell other parents how to help their own children.

One thing that I think my mother would have wanted to know was that we don’t always need to talk. Feeling suicidal can be extremely difficult to articulate, and I was always fearful of upsetting her if she knew what I was really feeling or thinking. Sometimes, I didn’t even know what I was feeling.

Physically sitting together—just being present and not talking—was usually what I needed most.

My parents often told me how special and amazing I was. They couldn’t help themselves; they wanted me to know it, and I could see how much it pained them to see that I didn’t. I remember how frustrated and upset I felt when they would tell me because I genuinely did not see it and could not believe it.

But what did help was when they told me that I would someday be able to see what they saw. That acknowledged that I thought otherwise, but gave me hope that I, too, would be able to see it one day.

I wish my parents had known when I was feeling my worst that it was not a reflection on how much they loved me or on their parenting, but instead on how much (or little) I valued myself. It was not anyone’s fault.

One of the hardest things for my parents was wondering if they could have stopped me. My suicidal ideation was a downward spiral, and I made small attempts to end my life. The farther down I spiraled, the less it seemed that intervention was possible. But my social worker was able to intervene and stop me from truly attempting to end my life.

When I was at my darkest point, I avoided becoming attached to people or passionate about anything because I did not want to miss anything or upset anyone if I chose to leave this world. Now I know that these connections are the most important things for me to have. I call them anchors. Anchors are things or people that I care about deeply.

I think about these anchors to remind me why I am alive.

My family is an anchor. My dogs are anchors. So are my friends and my therapists. I have passions that are anchors too, such as American Sign Language, suicide prevention, and raising self-esteem among adolescents.

I am on a constant journey towards achieving self-love. Although I am not at the point where I can confidently say that I love and accept myself, I know that I have value in this world, and that is enough for me to want to live. Through the hard work I put into my therapy, I am able to determine when I am feeling like I want to give up, compared to when I am feeling like I am a danger to myself, and that allows me to reach out for the help I need.

Stacy Brief is now 20 and studying social work at Adelphi University. She is dedicated to helping others and working to prevent suicide.

PARENT | Lisa Brief

PARENT | Lisa Brief

Confident, caring, sweet, motivated. Those words were used to describe Stacy by anyone who knew her. But nobody knew what was behind the sweet smile. She didn’t let anyone see the lack of confidence, the pain, or the loneliness. She had friends, was great in school, played sports, had interests, and spent time with family.

Around the age of 13, we began to see signs that something was off.

She didn’t go out with friends as often. If she did, she’d call to come home early. She retreated to her room and spent a lot of time alone and sad. Her legs shook uncontrollably. More concerning signs were seeing Stacy glued to social media (which had never been her thing) to see what other kids were doing that she wasn’t.

All of a sudden, she was “cold” all the time. She was wearing long sleeves and covering up more than usual and more than necessary to hide the hash marks of her self-harm. She frequently had “headaches,” an excuse to stay home from school or cancel plans. Then we noticed her lack of interest in food. She pushed the food around her plate. She thought if she got skinny, she would fit in better.

Through it all, the hardest part was that she would not open up to us. We later learned that she felt she didn’t fit in anywhere, not with friends, not even with her family. That was tough to hear and heartbreaking to think she felt she didn’t belong with us—her family who loves her fiercely.

I received a phone call at work from the high school social worker halfway through her freshman year. Stacy gave her a razor blade and confided in her that she was afraid she’d hurt herself and that she had a suicide plan. That night, we had to leave her scared, alone, and crying, in a pediatric psychiatric hospital. That was the most heart-wrenching night of my life. We knew she had to be in a safe environment.

We spent the night wondering when and where we had gone so wrong.

Not much changed at first. She still didn’t want to talk to us much, but at least she spoke regularly and willingly to the social worker and began a medication regimen to help fight depression, anxiety, and bipolar disorder. She tried to go to school but couldn’t make it through more than two or three periods without having an anxiety attack and fearing she’d hurt herself.

We couldn’t continue to put her through that, so we researched options for her. Stacy started by attending a “partial” program; she spent part of her day doing school work and part attending therapy and group sessions. After being homeschooled for the remainder of her school year, we were lucky enough to find a small, therapeutic high school. The school offered academics, therapy, and a safe environment.

We advocated for her needs, she began to speak up for what she wanted in her schooling, and we tailored a program to fit what Stacy needed to feel comfortable.

We also learned that, although kids deserve privacy, sometimes it is necessary and okay to violate that privacy for their own safety. We knew we needed to monitor her social media, messages, and texts. We saw she was communicating with girls we’d never heard of. They were girls in similar situations, but they were giving her new ways and ideas of how to harm herself. Because of that, we learned what things could not be left around the house and what further monitoring was necessary.

Slowly, Stacy began to spend more time with family again. We’d play games, watch movies, and go for walks or out for ice cream.

We kept her occupied.

She developed some new hobbies—painting, baking, and sign language. She learned that keeping busy was her best defense against her own dark thoughts and urges.

It’s true that it takes a village to raise a child. Stacy was very fortunate to find an amazing group of people to be part of her village. We are so grateful for the group of social workers at both schools and the group of teachers who became her friends, confidantes, and part of our family. Those bonds are now forever.

The high school administration team was amazing, too. They were happy to spend time talking with us, encouraging Stacy, listening to her needs, and helping any way they could. They showed concern and support for not only Stacy but for the whole family. Stacy also had a family friend that she often turned to, and we had friends who supported us and encouraged us to keep doing what we were doing to help her.

We are most grateful for every day that Stacy is still with us, and that she feels she has purpose in life. She has become an advocate for mental health and has taken on suicide prevention as her purpose and her message. We couldn’t be happier for her or prouder of her. We are thankful we get more time to love her.

Lisa Brief is a loving, hardworking mother of three children who works to support the prevention of suicide.

EXPERT | Stephen Sroka

EXPERT | Stephen Sroka

Suicide is a serious risk for teens. According to the latest Youth Risk Behavior Survey by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 17 percent of 9th through 12th grade students seriously considered suicide, 15 percent made a plan in the past year, and 9 percent attempted suicide. Suicide is the second leading cause of death among adolescents aged 15-19 years.

Advice for Families:

Based on my experiences with suicide research and prevention, I can offer other families the following information:

1. Reassure them that they are not alone.

The three words “you’re not alone” give parents and teenagers faced with a paralyzing suicide situation hope, energy, resilience, and a foundation to move forward. You’re not alone is the first answer to the cries for help.

2. Know that suicide is complicated. Suicidal people do not fit molds.

It is more than just the stress of tough times. Most teens, even those living stressful lives, do not become suicidal. But for some dealing with mental health issues or traumatic experiences, suicidal behaviors may surface.

Mental illness often plays a role. Suicide can be a preventable loss—if a teen dies by suicide, it is possibly the result of untreated or undertreated mental illness, such as major depressive disorders, bipolar disorder, and substance abuse problems.

Contributing factors can vary. Bullying may be a contributing factor, but there is not enough evidence to say that it alone can be the cause. A family history of suicidal behavior may be a risk factor, as may child abuse, neglect, and trauma. Access to a weapon, alcohol, or drugs, especially in the home, are risk factors.

3. Denial is a hurdle to healing.

Cries for help are often subtle and overlooked. Many parents say, “My teen will never be suicidal,” but denial is common in parents of suicidal teens.

4. Know the signs.

How do you know if your teen is at risk, or just being a normal teen with puzzling behaviors?

If you suspect, inspect. Look at their rooms, social media, and friends.

Ask about the severity of suicidal ideation. Talking about suicide will not make someone complete a suicide. If a teen has specific plans and strong intent, those are huge warning signs. Get help as soon as possible.

5. If in doubt, get help.

Do not try to assess the risk yourself. It is the job of a licensed health professional to assess the risk level. Medically assisted treatment may be prescribed, as well as physical movement and counseling (walk and talk therapy).

It is better to err on the side of caution than to suffer the potentially grave consequences. Suicide cannot always be accurately predicted. Love alone won’t fix it. Professional interventions can help.

6. Recovery is possible.

Offer the teen hope and support to move on, and let them know things will get better.

After a suicidal situation, help is available from school-based mental health professionals such as school psychologists, counselors, social workers, and nurses. Community clinics may offer mental health counseling and emergency psychiatric screening services. Personalized recovery programs based on individual needs can also help ensure success.

Interventions may be needed multiple times; there is no timeline for needing support.

As Stacy mentioned, anchors—things that have deep meaning, often called protective factors—like family, friends, faith, and even pets can help you from going adrift in the river of risky behaviors. Routines and keeping busy are cornerstones against relapses. Becoming an advocate for suicide prevention, as Stacy has done, can also be healing.

And, of course, it helps to spread that key message to other teens: You’re not alone.

FREE Crisis Suicide Lines:

National Suicide Prevention Lifeline

1-800-273-TALK (8255)

Crisis Text Line

Text HOME to 741741

The Trevor Project for LGBTQ+

1-866-488-7386

Immediate Danger

Call 911

TEEN | Stacy Brief

TEEN | Stacy Brief PARENT | Lisa Brief

PARENT | Lisa Brief EXPERT | Stephen Sroka

EXPERT | Stephen Sroka