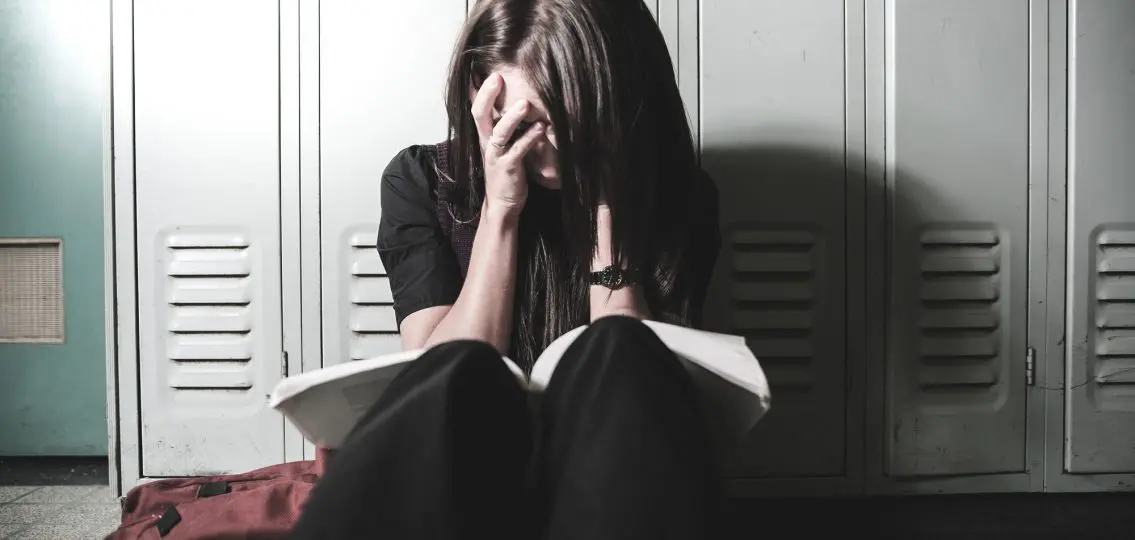

Rachael had been bullied at school over her emo friends and alternative appearance. And after a cruel confrontation with a boy one day at the end of eighth grade, she locked herself in her bathroom and cut her wrist with a razor.

She wasn’t trying to end her life; she was seeking relief from feelings of sadness, loneliness, and fear.

“It felt like a release of all this tension in my head, and even if it was just blood, it felt like I was getting rid of all of these voices that were telling me what was wrong with me,” Rachael says.

She eventually began cutting every day, which made her feel better and more in control for a bit before the bad feelings returned.

“It made me feel lighter and like the weight of the world wasn’t just on me,” she recalls. Rachael kept cutting through part of tenth grade but as a 16-year-old junior is now doing better. “It was almost like a high. But it wasn’t hurting anybody else, and it wasn’t illegal, so it was better than what most kids did.”

Why Teens Engage in Self-Harm

Cutting is a common form of what experts call non-suicidal self-injury. It involves using a sharp implement—such as a knife, a razor, a safety pin—to cut the skin as a way to relieve or cope with emotional pain; the goal is not suicide.

“Kids who cut are trying to feel better emotionally,” says Janis Whitlock, director of the Cornell Research Program on Self-Injury and Recovery. “They’re trying to make physical what they feel inside.”

Though children as young as seven or eight have been known to cut, the behavior is more typical in children ages 12 to 17 and young adults, says Whitlock. The average age that adolescents start cutting is 15.

Why self-harm? Cutting can provide a quick, but short-lived escape from psychological pain and stress. When the body is injured, its natural defense is to release pain-fighting endorphins, says Denise Ben-Porath, a psychology professor at John Carroll University who has treated teens who cut.

“They get the endorphin rush. And by doing that, it actually reduces the psychological pain,” adds Ben-Porath, explaining a common theory for how cutting helps people feel better.

For kids who feel emotionally numb, cutting may also help them feel alive. “Cutting is a way to remind themselves that they’re real,” Whitlock says.

It’s hard to know exactly how many teenagers cut. Research suggests an estimated 20 to 25 percent of American middle and high school-age kids have self-injured at least once, Whitlock says. And an estimated 10 to 12 percent of kids in that age range hurt themselves regularly.

Here’s some information for parents:

1. How do you know if your child is cutting?

Kids often cut parallel lines or sometimes words or symbols into their arms, legs, or stomach. Sometimes they can hide the signs of self harm. They often cut in private and hide their wounds, feeling shameful.

Signs of self harm include wearing wristbands, donning long sleeves or pants when it’s unseasonably warm, and hiding implements in their bedrooms. Rachael covered her cuts with bracelets when it was hot.

2. How can you help prevent your child from self-injuring?

To prevent teens from self-injuring, Whitlock suggests parents serve as role models for dealing with the difficult emotions in healthy, honest ways. Ben-Porath also recommends talking to kids about cutting just like you would about sex and drugs, so they know what it’s all about before they encounter it.

3. What should you do if your child is cutting?

Discovering your child is cutting can be terrifying. But it’s important to remain calm and get help from an expert experienced in working with adolescents. Ben-Porath suggests if you discover signs of self harm, you say something like, “This is what I’ve noticed on your arms. I understand when people do this, they’re in a lot of pain. I want to help you.”

Though some parents dismiss cutting as a cry for attention, it should not be ignored. For teenagers who have moved past an experimentation stage, cutting can become habitual and addictive. And it usually does not get better without treatment, says Ben-Porath.

A common, effective treatment is dialectical behavior therapy. This is a form of talk therapy that aims to replace cutting with healthy coping skills.

Parents should also understand that while cutting is considered a non-suicidal form of self-injury, people who cut are nevertheless at a greater risk for suicide, according to experts. Rachael became suicidal, told her father, and was hospitalized for a week in the fall of tenth grade. She, too, says parents should seek outside help for their teenagers.

“It’s a hard time in their life,” Rachael says. “But they just need someone to help them realize it’s not as bad as it seems.”